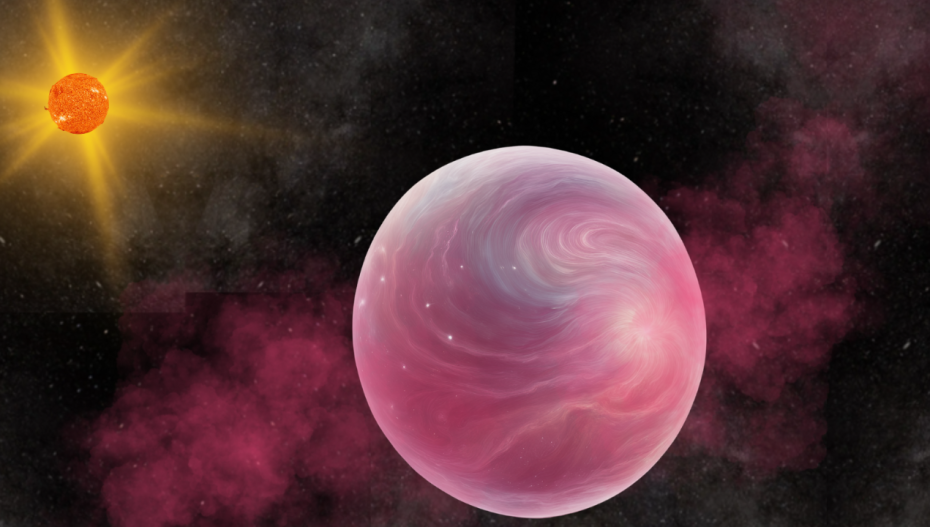

Astronomers have discovered a fourth world in a strange system of ultralight “super puff” planets using the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST).

The new extrasolar planet, or “exoplanet,” was discovered around the sun-like star Kepler-51, located 2,615 light-years away in the constellation of Cygnus (the Swan).

Remarkably, the new world, designated Kepler-51e, isn’t just the fourth exoplanet found orbiting this star; all these other worlds are cotton-candy-like planets. This could be a whole system of some of the lightest planets ever discovered.

“Super puff planets are very unusual in that they have very low mass and low density,” team member Jessica Libby-Roberts of Penn State’s Center for Exoplanets and Habitable Worlds said. “The three previously known planets that orbit the star, Kepler-51, are about the size of Saturn but only a few times the mass of Earth, resulting in a density like cotton candy.”

Libby-Roberts added that the team theorises that these cotton-candy planets have tiny cores and huge, puffy hydrogen or helium atmospheres.

“How these strange planets formed, and their atmospheres haven’t been blown away by the intense radiation of their young star has remained a mystery,” she added. “We planned to use the James Webb Space Telescope to study one of these planets to help answer these questions, but now we have to explain a fourth low-mass planet in the system!”

Kepler-51: A sweet star system

When a group of scientists from Penn State and Osaka Universities decided to investigate the characteristics of Kepler-51d, its lightweight twin, they found the fourth resident of this peculiar planetary system.

When Kepler-51d seemed to cross the face of its parent star or make a transit two hours earlier, the crew was taken aback.

Because different elements in a planet’s atmosphere absorb light at specific wavelengths when starlight streams past it, transits are helpful to astronomers. This implies that they leave their “fingerprint,” which enables astronomers to analyse the wavelengths of light observed to ascertain the composition of the atmosphere and other planet features.

The team’s estimations were off by 15 minutes, and astronomers are used to planets making transits either a few minutes early or a few minutes late. However, a two-hour mistake cannot be explained by that.

After correctly predicting Kepler-51d’s transit in May 2023 using their three-planet model, they anticipated it would transit at 2 a.m. EDT in June 2023. Using the Apache Point Observatory (APO) telescope and James Webb Space Telescope, the researchers prepared to watch the event. When the transit didn’t go as planned, they were taken aback and returned to their data to discover it had already happened.

“Thank goodness we started observing a few hours early to set a baseline because 2 a.m. came, then 3, and we still hadn’t observed a change in the star’s brightness with APO,” Libby-Roberts stated. “After frantically re-running our models and scrutinising the data, we discovered a slight dip in stellar brightness immediately when we started observing with APO, which ended up being the start of the transit — 2 hours early, which is well beyond the 15-minute window of uncertainty from our models!”

The team looked to ground-based telescopes and space archive data to explain why they had nearly missed the James Webb Space Telescope’s transit, and they concluded that the existence of an unexplored world was the best explanation.

Kento Masuda, a team member and associate professor of earth and space science at Osaka University, stated, “We were perplexed by the early appearance of Kepler-51d, and no amount of fine-tuning the three-planet model could account for such a large discrepancy.” “This discrepancy was only explained by the addition of a fourth planet. This is the first planet found with JWST through changes in transit timing.

Kepler-51d’s early transition can be explained by how this world affects the orbits of the other planets in the system.

“We conducted a ‘brute force’ search, testing out many combinations of planet properties to find the four-planet model that explains all of the transit data gathered over the past 14 years,” Masuda said. As we would anticipate from other planetary systems, we discovered that the signal is best explained if Kepler-51e has a mass comparable to the other three planets and orbits in a reasonably circular path of roughly 264 days.

“Other possible solutions we found involve a more massive planet on a wider orbit, though we think these are less likely.”

How does a star collect planets made of cotton candy?

When the scientists modified their models to include the new planet, they had to reduce the anticipated masses of the Kepler-51 system’s other planets.

This also affects theories about the other characteristics of these planets and the formation of such an odd planetary system. Before confirming that Kepler-51e is a super puff planet, the researchers must wait for it to transit its star.

According to Libby-Roberts, “super puff planets are fairly rare, and when they do occur, they tend to be the only ones in a planetary system.” “If it wasn’t challenging enough to explain how three super puffs developed in one system, we now have to clarify whether or not a fourth planet is a super puff. Furthermore, we must consider the possibility of other planets in the system.

The system will need more observation time before astronomers can be sure of how the new planet’s gravity affects its sibling worlds because Kepler-51e has a 264-day orbit.

“Kepler-51e has an orbit slightly larger than Venus and is just inside the star’s habitable zone, so a lot more could be going on beyond that distance if we take the time to look,” Libby-Roberts said. “Continuing to look at transit timing variations might help us discover planets that are further away from their stars and might aid in our search for planets that could potentially support life.”

The Astronomical Journal released the team’s findings on Tuesday, December 3.

Also Read: Allu Arjun’s Pushpa 2 Smashes Records: Becomes Highest Indian Opener Ever