The Amazon conglomerate that started as a book store to a multinational technology company that primarily focuses on e-commerce and streaming has been over and over accused of knocking off items it sells on its site and of taking advantage of its tremendous stash of internal data to advance its own merchandise at the expense of other sellers. The company has denied all the allegations.

However, examined by Reuters, thousands of pages of internal Amazon documents that include emails, strategy papers and business plans show that it ran a systematic campaign by creating knockoffs of best seller products and manipulating search history to boost its own product lines in India – one of the country’s largest growing markets.

The archives uncover how Amazon’s private-brands group in India subtly took advantage of internal information from Amazon.in to duplicate items sold by different organizations, and afterwards offered them on its site. The representatives likewise stirred up deals of Amazon private-brand items by rigging Amazon’s search lists with the goal that the organization’s items would show up, as one 2016 strategy report for India put it, “in the initial 2 or three … “search results” when clients were shopping on Amazon.in.

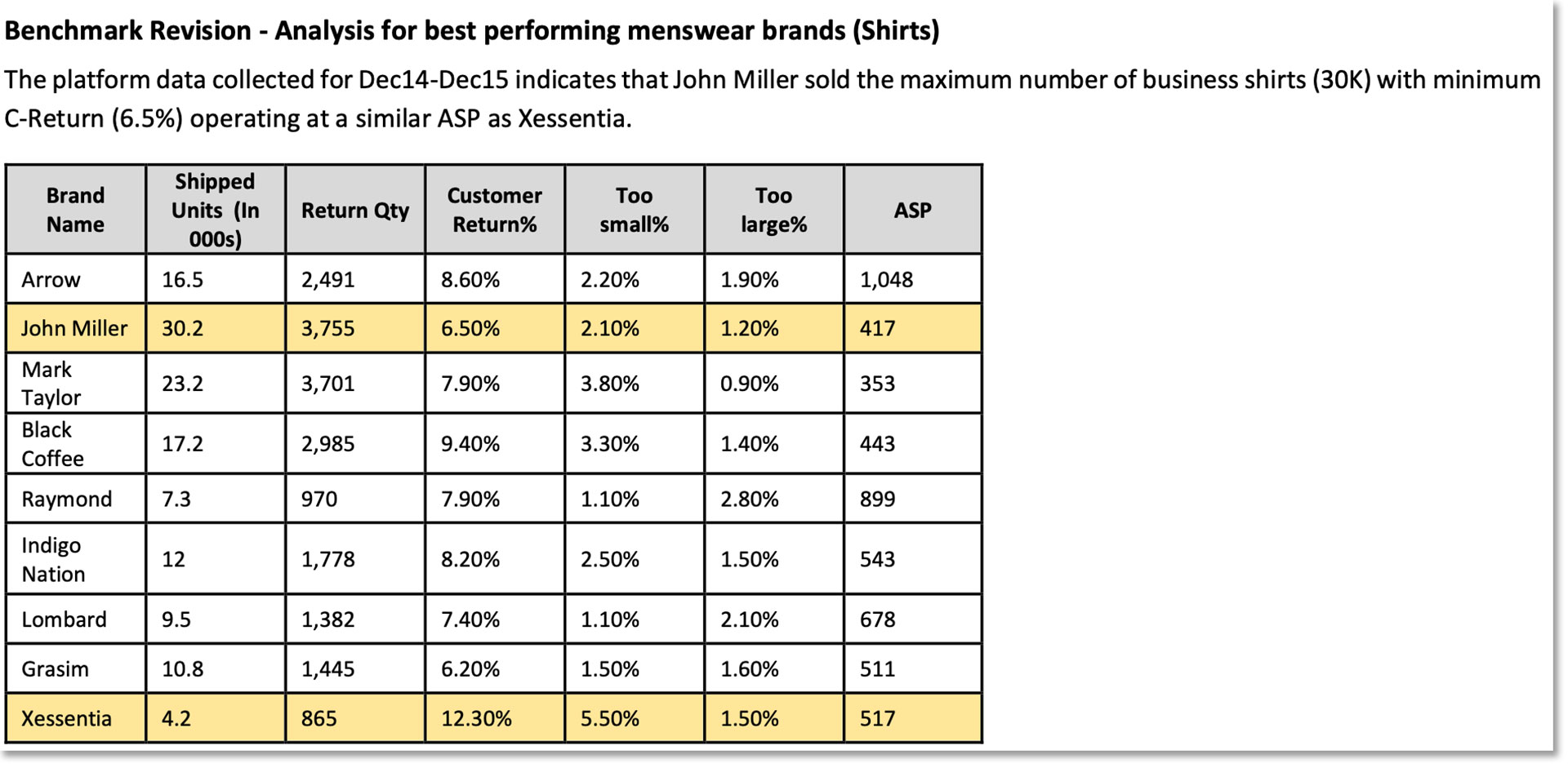

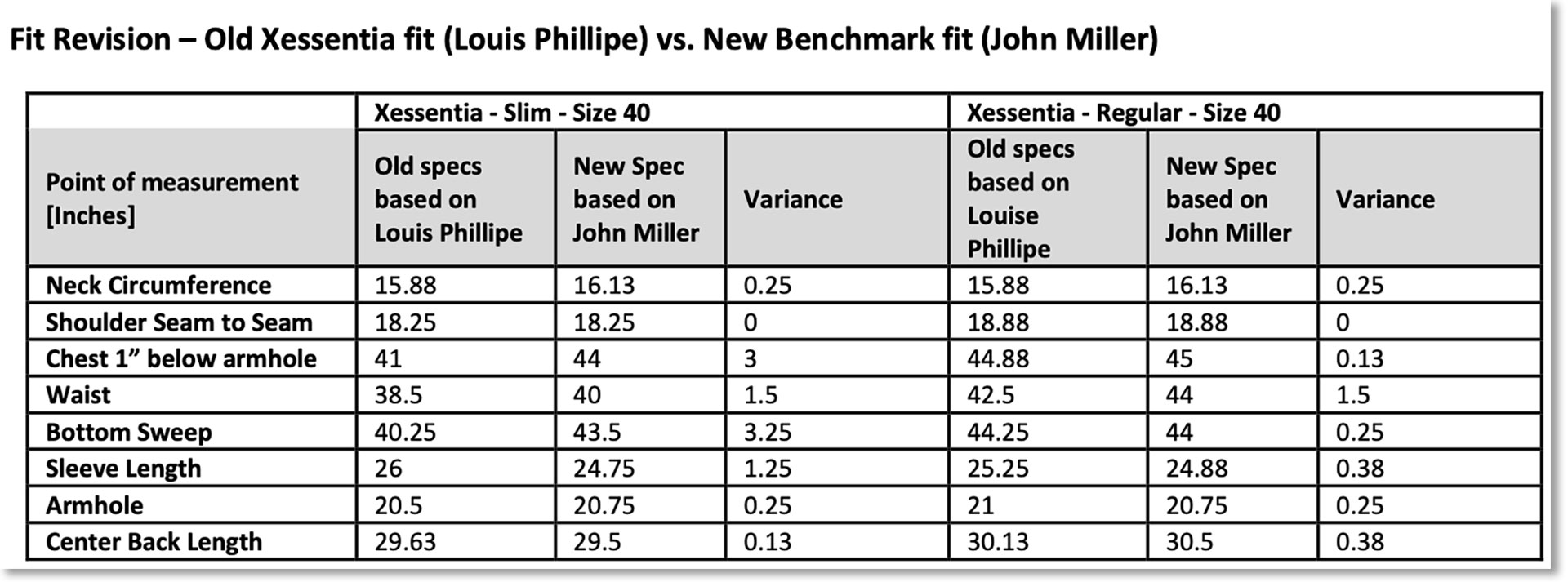

Among the victims of the technique: a famous shirt brand in India, John Miller, which is possessed by a company whose CEO is Kishore Biyani, known as the country’s “retail king.” Amazon chose to “follow the measurements of” John Miller shirts down to the neck circumference and sleeve length, the report states.

The documents additionally show that Amazon workers studied exclusive information about different brands on Amazon.in, including definite data about client returns. The aim was to recognize and target merchandise – depicted as “reference” or “benchmark” items – and “replicate” them. As a feature of that work, the 2016 inside report spread out Amazon’s technique for a brand the company initially made for the Indian market called “Solimo”. The Solimo methodology, it said, was simple: “use data from Amazon.in to leverage the Amazon.in platform to advertise these items to our customers.”

The Solimo project in India has had a worldwide effect: Scores of Solimo-marked wellbeing and family items are currently made available for purchase on Amazon’s US site, Amazon.com.

The 2016 record further shows that Amazon representatives chipping away at the organization’s own items, known as private brands or private labels, wanted to band together with the makers of the items focused on replicating. That is because they discovered that these makers utilize “unique processes which impact the end quality of the product.”

The record, named “India Private Brands Program,” states: “It is hard to foster this expertise across products and hence, to ensure that we are able to fully match quality with our reference product, we decided to only partner with the manufacturers of our reference product.” It termed such manufacturer expertise “Tribal Knowledge.”

This is the second in a progression of stories dependent on internal Amazon archives that give an uncommon, unvarnished look, in the organization’s own words, into business practices that it has denied for quite a long time.

Amazon has been denounced before by employees who chipped away at private-brand products of taking advantage of restrictive information from individual dealers to dispatch contending items and controlling search results to build sales of the organization’s own merchandise.

In a sworn declaration before the U.S. Congress in 2020, Amazon founder Jeff Bezos clarified that the e-commerce giant prohibits its workers from utilizing the information on individual dealers to help its private-label business. Furthermore, in 2019, another Amazon chief affirmed that the organization doesn’t utilize such information to make its own private-label items or modify its search lists to lean toward them.

Yet, the internal archives seen by Reuters show interestingly that, basically in India, controlling search items to incline toward Amazon’s own items, just as duplicating other venders’ merchandise, were essential for a formal, surreptitious system at Amazon – and that undeniable level leaders were told about it. The archives show that two chiefs inspected the India procedure – senior VPs Diego Piacentini, who has since left the company, and Russell Grandinetti, who as of now manages Amazon’s international customer business.

In a written response to inquiries for this report, Amazon said:

“As Reuters hasn’t shared the documents or their provenance with us, we are unable to confirm the veracity or otherwise of the information and claims as stated. We believe these claims are factually incorrect and unsubstantiated.”

The company didn’t go into details. The assertion additionally didn’t resolve inquiries from Reuters about the proof in the records that Amazon employees replicated other company’s items for its own brands.

The company said the manner in which it shows list items doesn’t incline toward private brand items. “We display search results based on relevance to the customer’s search query, irrespective of whether such products have private brands offered by sellers or not,” Amazon said.

Amazon likewise said that it “strictly prohibits the use or sharing of non-public, seller-specific data for the benefit of any seller, including sellers of private brands,” and that it researches reports of its representatives disregarding that strategy.

Piacentini and Grandinetti didn’t react to requests for input.

The unfiltered knowledge the records offer into Amazon’s forceful utilization of its market force could strengthen the lawful and administrative tension the organization is looking at in numerous nations.

Amazon is being scrutinized in the United States, Europe and India for the supposed enemy of cutthroat practices that hurt different organizations. In India, the charges incorporate unjustifiably leaning toward its own marked product. Amazon declined to remark on the examinations.

Jonas Koponen, an antitrust lawyer with Linklaters LLP in Brussels, said the Reuters discoveries on Amazon’s practices in India would probably intrigue the European Commission, which is testing whether the company has utilized non-public seller information to help its own retail business. India has collaboration concurrences with the United States and the European Commission to trade data identified with authorization of antitrust laws.

“When anyone competition authority is looking into aspects of one of these globally present organizations’ behaviour, they will certainly be interested in understanding what evidence there is in other parts of the world and the extent to which that evidence relates to the practices that they themselves are investigating,” Koponen said.

The records additionally support analysis of Amazon spread out by Lina Khan, the new chair of the U.S. Government Trade Commission (FTC). Khan distributed a paper in 2017 that contended that Amazon’s private-brand business raised anti-competitive concerns.

“It is third-party sellers who bear the initial costs and uncertainties when introducing new products; by merely spotting them, Amazon gets to sell products only once their success has been tested,” she wrote. “The anti-competitive implications here seem clear. “

Amazon filed a petition in June with the FTC asking that Khan recuse herself from all matters identified with the company in view of “her repeated proclamations that Amazon has violated the antitrust laws.”

Khan and the FTC didn’t react to requests for input.

In the first article in this series, Reuters revealed in February that Amazon had for quite a long time given special treatment to a couple of large vendors on its Indian platform, and utilized those merchants to evade guidelines intended to secure the country’s little retailers. That report set off the activity of India’s main financial crime-fighting agency, which looked for data and records from Amazon. Also, the country’s antitrust guard dog presented the story as a display in a court fight with Amazon over its examination concerning the organization’s supposed anti-competitive practices. The court dismissed Amazon’s solicitation to end the test.

“We are committed to extending cooperation to all authorities in India and are confident about our compliance,” Amazon said in its assertion to Reuters.

In the same way as other different retailers, Amazon sees its own brands as a significant driver of expanded profitability. Private-brand items frequently have higher overall revenues than typical retail marks since creation and showcasing expenses can be lower.

Presenting Amazon’s own brands was particularly critical in India. The company started its web-based business invasion there in 2013 and recorded a large number of dollars in losses, one internal report shows. To make the business “sustainable in the long run,” the 2016 Private Brands document notes, Amazon set out on a technique fixated on presenting its current private brands, like AmazonBasics, and new one’s custom-fitted to India.

The 2016 report expressed an objective: offer Amazon’s own merchandise in 20% to 40% off all item classifications on Amazon.in within two years. Amazon would accomplish profitability in its private-brand business by “only launching products that will provide more margin than comparable reference brand products.”

Amazon anticipated private-brand deals would reach almost $600 million by 2020 in India, as indicated by a 2017 internal business strategy document. “We will be amongst the Top 3 brands in each sub-category that we play in,” the record expressed.

Regardless of whether it accomplished that business objective isn’t clear; Amazon doesn’t unveil its private-brand deals in India. The company didn’t remark on the strategic goals and different subtleties from the archives detailed in this article.

An Amazon press release in 2018 uncovered exactly how fruitful its private-brand business was becoming in India. Praising “record sales” during a yearly advancement, the release stated, “Amazon Brands saw its best performance ever with 11X jump over last Great Indian Festival.”

Today, Amazon.in records many Amazon-branded contributions – from trash containers, bedsheets and cleansers to climate control systems and TVs. As indicated by the site, many are bestsellers.

One key individual associated with 2016 with Amazon’s private-brand business in India was Amit Nanda, who later turned into a country overseer of the program, as indicated by his LinkedIn profile. He holds an MBA from the Indian Institute of Management, Ahmedabad, one of the country’s top business schools. Prior to joining Amazon in 2014, as indicated by his LinkedIn profile, he worked at Citibank and the Indian arm of customer products giant Unilever.

As Amazon was checking on its private-brand strategy in India in 2016, Amazon India representatives had a gathering with Grandinetti. A long-term Amazon manager, at the time he was accountable for content for Kindle, the company’s famous reading gadget. Yet, Amazon had declared that he would before long lead its global customer business, including India.

During the gathering, Nanda was relegated to different tasks, as indicated by one Amazon record. Among them: should be large and profitable. Build for scale.”

Nanda declined to remark for this story.

Glance views

With its populace of 1.3 billion individuals and a developing working class, India addresses a tremendous and conceivably worthwhile market for Amazon. But on the other hand, it’s a nation where unfamiliar internet business players face a complex and protectionist administrative system.

The nation’s physical retailers include a significant political voting public for Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi. Worried that savage valuing could hurt these traders, India precludes unfamiliar online business players from selling most merchandise straightforwardly to customers, as they do in numerous different nations. Amazon and other unfamiliar companies are limited to working a web-based commercial center of outsider dealers, with nobody merchant permitted to hold a benefit over another. Therefore, Amazon sells the majority of its private brands through different merchants.

In dispatching its private-brand business, internal reports show how Amazon utilized its Indian site to acquire a reasonable edge for its own items on the platform. The production of its Solimo brand offers a contextual analysis.

As indicated by the internal records, the word Solimo is gotten from Solimões – the name for the upper stretches of the Amazon River in Brazil.

With the Solimo line, Amazon expected to offer things that rose to or surpassed the nature of competing brands yet were 10% to 15% cheaper, the 2016 Private Brands record shows. Amazon workers studied various product categories and contrasted their overall market size and how well those segments were doing on Amazon.in. They then, at that point, targeted classifications like home furnishings. Amazon observed that goods was a $2 billion business in India – yet its own site’s three-month deals in mid-2014 added up to about $1 million.

In its investigation, Amazon utilized a measurement called “glance views” that evaluated which items were being seen by clients on its site. Clarifying why it zeroed in on glance views, the 2016 Amazon archive noticed that checking its India site traffic gives “an opportunity to influence interested customers who are actively considering” a purchase in a product category.

Amazon has said a portion of the information its private-brand groups use in dispatching items is public – like the site’s rankings of top-rated merchandise. This is the manner by which Amazon depicted the framework to a U.S. congressional subcommittee last year:

“Like anyone else at Amazon or in the general public, members of these teams can also visit Amazon’s product detail pages to learn a product’s bestseller ranking and read customer reviews and star ratings to assess whether a product is selling well in Amazon’s store.”

Yet, seven current and previous Indian dealers on Amazon.in told Reuters they can’t get to internal deals information of opponent brands presented on the site. Four of the vendors said they can access glance views, however just for their own items. Amazon has access to more information on merchants, including the number of item units transported and insights concerning client returns, the 2016 archive shows, giving it a benefit in market knowledge.

Amazon’s own utilization of the information to create and advance its private-brand items “destroys the level playing field,” said one current dealer, who requested to stay unknown.

Amazon said in its explanation that it “does not give preferential treatment to any seller on its marketplace.” The company also said it “identifies selection gaps based on customer preferences at an aggregate level only and shares this information with all sellers.”

How to ‘replicate’ products

When Amazon’s private-brand representatives had concluded which categories to enter, they inspected deals and client audit information on Amazon.in to distinguish “reference” or “benchmark” brands to “duplicate,” the 2016 private-brand record showed.

On account of Solimo, the 2016 record expressed that to guarantee the brand’s merchandise meet “customer requirements in terms of performance we identify and replicate these reference products.” Amazon had no remark on the Solimo project.

Amazon’s technique additionally called for makers of its private-brand items to utilize other organizations’ merchandise as models to foster examples for pre-production testing.

Among the brands Amazon workers wanted to “benchmark,” the report states, were American ones – “Old Navy/GAP” men’s shirts. The record doesn’t demonstrate whether the representatives finished.

Gap Inc, which possesses the Old Navy and Gap brands, declined to remark.

The rival items Amazon designated likewise included different brands well known in India. For pots and pans, a “reference brand” was Prestige, one of India’s biggest kitchen-gear companies. For men’s shirts, the benchmarks included Peter England and Louis Philippe, both made in India by aggregate Aditya Birla Group.

Amazon additionally targetted John Players, a menswear brand then, at that point, possessed by Indian conglomerate ITC Ltd.

Chandru Kalro, overseeing head of TTK Prestige, which claims the Prestige brand in India, told Reuters,

“We have no knowledge of us being a ‘reference brand’ for Amazon and we don’t know what it means to be an Amazon reference brand.”

Aditya Birla Group declined to remark. ITC didn’t react to a solicitation for input.

In early 2016, Amazon private-brand representatives were internally taking note of the achievement of Xessentia, a dress brand they had launched on Amazon.in in partnership with a dealer. The merchant claimed the brand; Amazon designed the items.

Deals of Xessentia men’s business shirts were flooding, and in the first quarter of 2016 had turned into that category’s second-most well-known brand on the India site after the American brand Arrow, authorized to the Indian company Arvind Fashions. To make the Xessentia line, Amazon had utilized Louis Philippe as the benchmark brand, since it was “premium and popular,” the 2016 archive said.

But something was amiss: About one in each 12 Xessentia shirts was being returned in the first quarter of 2016 for sizing issues. More than 350 were returned in light of the fact that clients complained they were excessively little.

Amazon representatives led a “deep dive,” the 2016 record reports, by poring longer than a year of information from Amazon.in, including client grievances and return numbers for Xessentia, Arrow and seven different brands. They observed that a brand of men’s business shirts in India called John Miller had far surpassed Xessentia shirts, in spite of conveying “a similar” average selling cost. John Miller additionally had about a large portion of the pace of client returns for “quality issues.”

The consequence: “Our learning is that our customer is different from the Louis Philippe customer and doesn’t prefer this fit,” the 2016 document stated. “We concluded to follow the measurements of Business Shirt of John Miller for Xessentia because of wide acceptance with our customer base”

So Amazon reexamined the fit of Xessentia shirts to duplicate John Miller’s measuring, coordinating with it down to the neck, shoulder, armhole, sleeve and midriff aspects.

Amazon didn’t answer to inquiries concerning its Xessentia project. Arvind Fashions declined to remark.

John Miller is a brand possessed by retail mogul Kishore Biyani. Amazon and Biyani later became colleagues in India, yet had an altercation. Amazon is presently entangled in a fight in court with Biyani over the proposed offer of his retail resources for Reliance, which is controlled by very rich person Mukesh Ambani, considered India’s richest man. Ambani and Amazon are savage opponents, with the Indian tycoon lately dispatching his own online business.

A representative for Biyani’s Future Group said the company was “shocked and surprised” to discover that Amazon was utilizing Indian brands to assemble its own. “They are in a powerful position of being both an online marketplace operator and a seller and collector of data,” the spokesperson said in a statement to Reuters. “This is leading to misuse of consumer and seller data giving them the power to kill Indian entrepreneurs and their brands.”

After the dispatch of Xessentia, Amazon presented a brand of U.S.- and European-style garments in India called Symbol.

“For every product line identified for launch, we will identify an optimal reference brand based on customer reviews and size of business,” state the plans for Symbol and another private brand. “The replication of the ‘Fit’ of this reference brand will be a crucial step in our product development process.”

The Symbol brand is as yet pushing ahead. On Oct 11, 11 of the main 25 top of the line men’s formal shirts on Amazon.in conveyed the Symbol brand name.

Systematic campaign of copying

Amazon has been repeatedly accused in the United States of copying product designs.

In 2018, home-goods retailer Williams-Sonoma Inc filed a federal lawsuit against Amazon, accusing the e-commerce giant of copying its proprietary designs for chairs, lamps and other products for an Amazon private brand called Rivet.

“Amazon has engaged in a systematic campaign of copying,” the lawsuit alleged. The exhibits filed in the case included pictures of similar-looking products from Amazon and a Williams-Sonoma brand. In court filings, Amazon denied the copying allegations. Last year, the two parties reached a confidential settlement. Both didn’t comment about the case for this story.

Joey Zwillinger, co-founder of Allbirds Inc, a San Francisco-based maker of sustainable footwear and apparel, told Reuters that around 2016 or 2017, Amazon began inviting his company to sell its goods on the e-commerce giant’s platform. Allbirds said no.

Then, in 2019, Amazon introduced a wool-blend sneaker that closely resembled a popular Allbirds wool shoe – and sold for much less. Zwillinger said the Amazon product used cheaper material but that the design was so similar, “it’s hard to tell the difference in a silhouette.”

Allbirds didn’t sue. “There are always subtle differences in designs, and copycat cases can be time-consuming”, Zwillinger said. But he and Allbirds’ other co-founder posted online a letter to Bezos, noting that the Amazon product was “strikingly similar to our Wool Runner” sneaker. Writing that Allbirds was “flattered at the similarities,” they offered to help Amazon use more sustainable materials in its product.

Zwillinger told Reuters that they didn’t receive a response. Amazon had no comment.

In India, Amazon didn’t just knock off products for itself. One of its employees suggested that another seller consider replicating a company’s products.

In 2020, Amazon India employee Aditi Singh advised Mohit Anand, who was then selling products on Amazon.in, on how he could succeed on the platform. She suggested that Anand “replicate” a furniture company’s products, according to a recording of a phone call reviewed by Reuters.

Noting that an Indian furniture brand called DeckUp was selling well on Amazon.in, Singh suggested that if Anand were to “replicate DeckUp’s range” and charge lower prices, then the products “will sell very well” on Amazon.in. Anand told Reuters that he didn’t take the advice.

Utheja Pulluri, DeckUp’s founder and a former Amazon India employee, said that as long as the e-commerce giant was “not sharing confidential data on us, I don’t have a problem … This appears to be business guidance, a generic insight.”

Singh referred a Reuters request for comment to Amazon’s public relations team. The company didn’t comment.

‘Search seeding’ and ‘sparkles’

How high products rank when customers search the Amazon website is critical to online sellers’ success. An internal document in 2017 noted that more than half of users’ clicks on search results are for the products listed in the top eight.

Amazon has said its search algorithms don’t favour its private-brand products. Asked during the 2019 congressional hearing whether Amazon alters algorithms to direct consumers to its own goods, associate general counsel Nate Sutton replied: “The algorithms are optimized to predict what customers want to buy regardless of the seller.”

Yet the internal Amazon documents show that in India, Amazon manipulated search results to favour its own products.

The company used a technique called “search seeding” to boost the rankings of its AmazonBasics and Solimo brand goods, according to the 2016 private-brand report. Referring to Amazon’s product codes – known as ASINs, or Amazon Standard Identification Numbers – the report stated: “We used search seeding for newly launched ASINs to ensure that they feature in the first 2 or three ASINs in search results.”

The document also referred to another technique that gave Amazon an edge: “search sparkles.” The 2016 private-brand report said.

“We have aggressively used search sparkles on PC, Mobile and App to specifically promote Solimo products on relevant customer searches from ‘All Product Search’ and Category search”

According to one current and two former Amazon employees, search seeding and search sparkles are digital techniques the company has used to direct customers to certain products.

Two of the sources said Amazon has used seeding to alter search rankings to boost products, such as new ones, whose sales are so low that there are insufficient data for the company’s technology to rank them. Sparkles are banners that Amazon has planted above search results to direct customers to certain products the company wants to promote.

While such tools have legitimate uses to assist online shoppers find certain hot new products, using search seeding to boost the rankings of Amazon’s own products hurts rival merchants’ sales on the platform, one of the former employees said.

Search seeding and sparkles were both used to promote AmazonBasics products on the company’s India platform, the 2016 document reveals. Within months of the launch of AmazonBasics in India in 2015, four of its products were “#1 Bestsellers in their category week after week,” the 2016 document said. It added that “promos” were placed on “detail pages of competitor products to direct traffic to AmazonBasics brands products.”

Piyush Tulsian, a New Delhi retailer of computer accessories, told Reuters he used to earn about $1,500 a month selling mousepads on Amazon.in made by Logitech International, which is headquartered in Switzerland.

Then, about two years ago, he said he started noticing that his sales were dropping. He said he discovered that customers who viewed details about the Logitech mouse pad he was selling for $21 were shown an advertisement for an AmazonBasics pad that was about 60% cheaper. The Logitech product also began appearing much lower in search results, he said.

“It’s very frustrating,” said Tulsian, who is 36. “They are mistreating sellers.” He said he stopped selling the Logitech mouse pad on Amazon.in and was stuck with 150 unsold ones.

Amazon had no comment. Logitech declined to comment.

Controversy over the business practices of foreign e-commerce companies in India has heated up in recent months. In June, the government proposed draft regulations that threaten to impose further restrictions on Amazon and other e-commerce companies, including local players, after receiving complaints by consumers and traders of unfair business practices. The proposed rules could restrict Amazon and others from selling their own private-brand products in India.

Later that month, India’s commerce minister accused large e-commerce companies of flouting local laws and said he had observed “a little bit of arrogance,” particularly by American ones. The other big platform in India is Flipkart, owned by American retail giant Walmart Inc. Flipkart didn’t comment.

In early July, Amazon announced it would introduce to India a program it already offers businesses elsewhere. Called the “Intellectual Property Accelerator” program, it gives certain sellers on Amazon.in access to services provided by intellectual-property experts and law firms.

One aim, Amazon said, is to help sellers “protect their brands.”

This story is by Reuters.