Finance minister Nirmala Sitharaman started the innings of her much-awaited 2022 budget speech by emphasising her macro-fiscal priorities.

Thus, we were treated to terms such as a vision of ‘India at 100’, in areas of ‘inclusive development’, ‘productivity enhancement’, ‘sunrise opportunities’, ‘energy transition’, ‘climate change’ and ‘PM Gati Shakti’.

The PM Gati Shakti Programme identified seven engines of growth: roads, railways, airports, ports, mass transport, waterways and logistics infrastructure. It appears these are the ‘engines of growth’ that the government feels committed to.

To enable a clearer understanding and reading of all key announcements made, it would be better to focus this analysis on three broader areas – job creation-job security, social welfare spending priorities (given the impact seen on vulnerable sections from COVID-19), and in identifying a clear fiscal consolidation plan.

On the first two areas (job security, social welfare spending), there is a clear disappointment.

On the third (fiscal consolidation), the government’s approach on choosing ‘expansion’ over ‘consolidation’ seems measured, but lacks clarity in terms of details on allocative redistribution of additional capex to states, and in enhancing capabilities of states to ‘spend’ and ‘consolidate’ more through the Centre.

On job creation and job security

It seems the Modi government’s indifferent approach with regards to addressing the puzzling crisis more directly will not change.

A long-term view of ‘India at 100’ for now remains centred on enhancing capital expenditure supported ‘growth’ and ‘productivity’ in big-infra segments, which the finance minister has remained rigidly tied to since the last Union Budget. The hope is the big boost in capital expenditure and more ‘supply side’ spending measures will subsequently create enough ‘good quality jobs’.

The Union government, as seen in the chart below, has upped its commitment to capital expenditure for this year too. On-budget expenditure has been raised to Rs 7.5 lakh crore, up 35.4% over last year’s budget estimate of Rs 5.5 lakh crore.

In the normal course of action, this long-term capital driven spending move might have been understood as a good way forward. Still, in times of crisis, when the employment generation machine across sectors is struggling, a solitary supply-side move may just not be enough.

Higher allocations to MGNREGA (already affected in 2021 by inadequate budgets), greater support to states for targeted job creation; enhancing PLI schemes towards ‘job creation’, and introducing an urban-version of a MGNREGA plan (at least at a smaller scale) were all seen as part of expectations to address the ‘joblessness’ crisis head-on. We didn’t hear about either of these, which is disappointing. Even worse, the finance minister did not even mention the ‘crisis’ of joblessness that’s afflicting the state of the Indian economy right now.

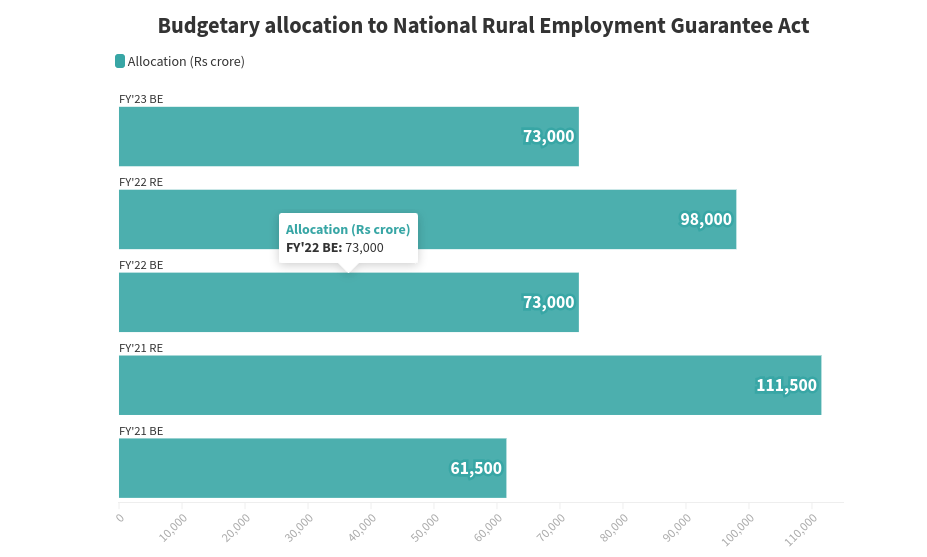

For MGNREGA, the rural jobs guarantee programme, the Union government has allocated only Rs 73,000 crore, even though it knows more will be required.

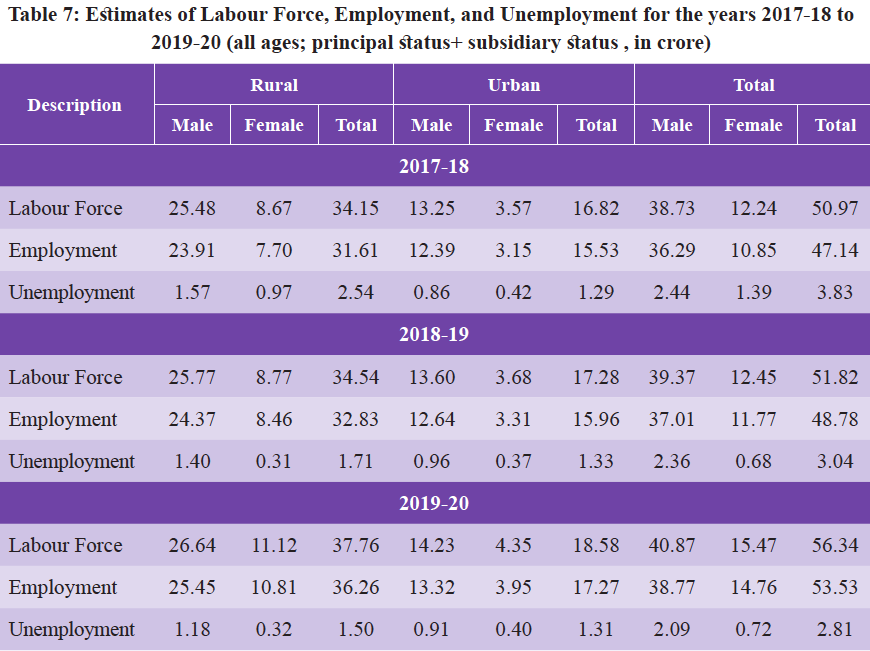

India’s broken labour markets and an asymmetric employment landscape (as seen in the figure below) has largely been split between the unorganised and organised space, with the latter being hit the most during the pandemic. It has also been the most resilient though, once the state-wide/national lockdowns were lifted.

Given the lack of jobs in the organised (formal) segment, the better treatment of the unorganised sector via protection of MSMEs has been vital.

Unfortunately, the second wave fiscal response measures by the government failed to do much to protect the affected MSMEs, adversely affecting employment in unorganised-organised sectors.

In the context of MSMEs, one of the larger job creating segments for both the unorganised-organised employment landscape, the only positive, for now, from the allocative announcements made was in the direction of extending the emergency loan guarantee (ECLGS) announced against the background of the COVID-19 crisis to support MSMEs. The scheme will now be extended till March 2023 and its guarantee cover will be expanded by Rs 50,000 crore to total cover worth Rs 5 lakh crore, said finance minister Sitharaman.

Is this enough? It’s unclear, but the scheme has provided immediate relief to small enterprises. The concern is that there is still no clarity on the quality of these loans, how they will be allocated, and the role of banks. It is also not clear whether scheduled commercial banks or public sector banks, already affected with ‘poor quality loans’ on their balance sheet and a weak IBC-driven recovery of old bad loans, will actually walk the talk on extending credit to the MSMEs in most-need.

With a high government debt to GDP ratio, the government would also need to ‘tread with caution’ in how it implements the credit guarantee allocations – as such guarantees will be a contingent liability on the government’s books.

On social welfare spending

In discussing ‘inclusive development’, the finance minister offered passing remarks on measures to be initiated by the government for enhancing ‘digital education’, ‘-e-courses’, ‘tele-mental-health programmes, and promote ‘women-empowered development’ through existing Nari-Shakti programmes.

That was it. One bright spot was that for FY 2022-23, the Union government has allocated Rs 1,04,278 crore for the education sector, which is 11,054 crore higher than the amount allocated to the education sector in the financial year 2021-22. Last year, the Union Budget allocated an amount of Rs 93,224 crore to the education sector. The revised estimate made this to be Rs 88,002 crore. This indicates an increase in the budgetary allocation for education by 11.86%.

It would be interesting to see how the allocation happens for this increased outlay as a slew of new schemes have been announced this Budget: say, a digital university to provide education in different Indian languages that will be built on a hub and spoke model, and a one-class one TV channel e-learning service. Compared to the extent of learning loss seen in education for young girls and boys over the last two years, a lot more was expected to be done in supporting educational institutions that have been adversely affected.

In this author’s pre-budget analysis, it was shown how dismal the Union government’s social welfare spending levels have been, even during the pandemic years.

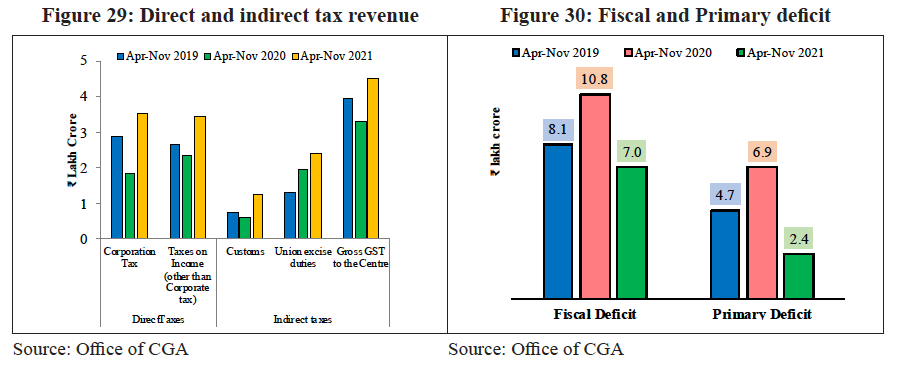

The Economic Survey 2021 report highlights it as well (see Figure below).

The combined aggregate spending in areas of education and healthcare (outside COVID-19) has been less than 9% of GDP. As percentage to total government expenditure, the aggregate expenditure on social services is around 26.6% (in education it is 9.7% and 6.6% in healthcare). The level of public expenditure in nutrition-centred programmes, including those focusing on early child development, has been dismally low.

The Government of India’s budgetary allocations have seen a decline in child-related departments from FY 2020-21 onwards. The Union Ministry of Women and Child Development saw a decline in budgetary spending from Rs 30,007.1 crore to Rs 24,435 crore. The budget for the Department of Education and Literacy was already slashed to Rs 53,600 crore from 59,370 crore. The budgetary allocation for child protection was cut down by 40% from Rs 1,500 crore to Rs 900 crore. This has affected the state’s abilities to spend on existing child-related programmes (see figure below).

Further, with states’ fiscal spending capabilities affected during COVID-19, the bulk of the responsibility of redistribution of additional resources towards social welfare, can fall directly on the Centre (Union) government’s head. That responsibility, it seems, has been abdicated by the Union government.

On fiscal consolidation

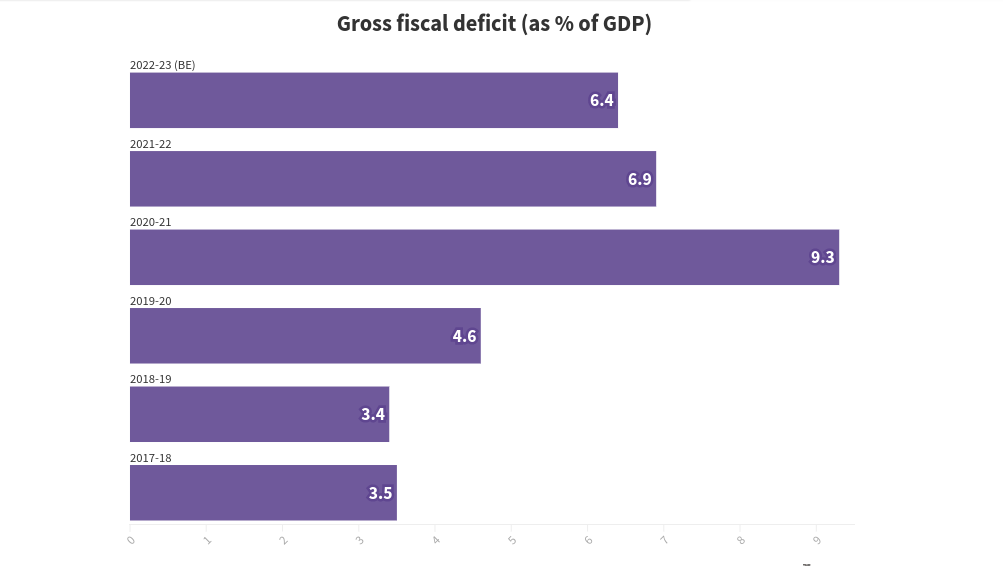

The Union government’s fiscal deficit for FY22 settled at 6.9% (see Figure below).

They have announced consolidation of 0.5 percentage points, which takes the FY23 fiscal deficit to around 6.4% (past data on deficit trends in Figure below). One can see an effort made this budget at some fiscal consolidation, but at a measured pace. This is understandable given the priority to spend more in a low private investment-consumption cycle.

For states, however, a fiscal deficit of 4% is being permitted again. This is also useful since state spending is critical in the next year. The government also plans to provide assistance of Rs 1 lakh crore over and above that. It was obvious that the government will focus on economic expansion over consolidation for now. However, the way the government decides to spend its resources and distributes it amongst states remains vital.

As Pinaki Chakraborty, director of NIPFP, pointed out in a recent interview: “Capital expenditure (capex) is a very important part of growth stimulus, but distribution of capex is also important. There, if we look at general government capex, then about two-thirds is at the state level,” adding that 13 states have reported revenue deficits for 2021-22 compared to seven or eight before the pandemic. He said: “It is very important that the reprioritisation happen at the aggregate level as well as at the individual state level.”

On this latter count, we didn’t get much clarity from the finance ministry this budget. Moreover, we don’t know how states – and the Centre – will support both ‘lives’ and ‘livelihoods’ of those affected by the pandemic and its economic crisis. About 80% of the redistributive expenditure needs to be at the state level, which isn’t the case.

In summation, both the 2022-23 budget and the finance minister’s ‘India at 100’ long-term vision blindly ignored – without making a mention – the need for establishing a robust social and economic safety net for the most vulnerable populations and communities across India.

Deepanshu Mohan is associate professor of Economics and director, Centre for New Economics Studies (CNES), Jindal School of Liberal Arts and Humanities, O.P. Jindal Global University.

This article was published by The Wire

Unclear how many of us will be around to light 100 candles on the birthday cake.